Heading into COP, Brazil’s Amazon deforestation rate is falling, as are areas affected by fire

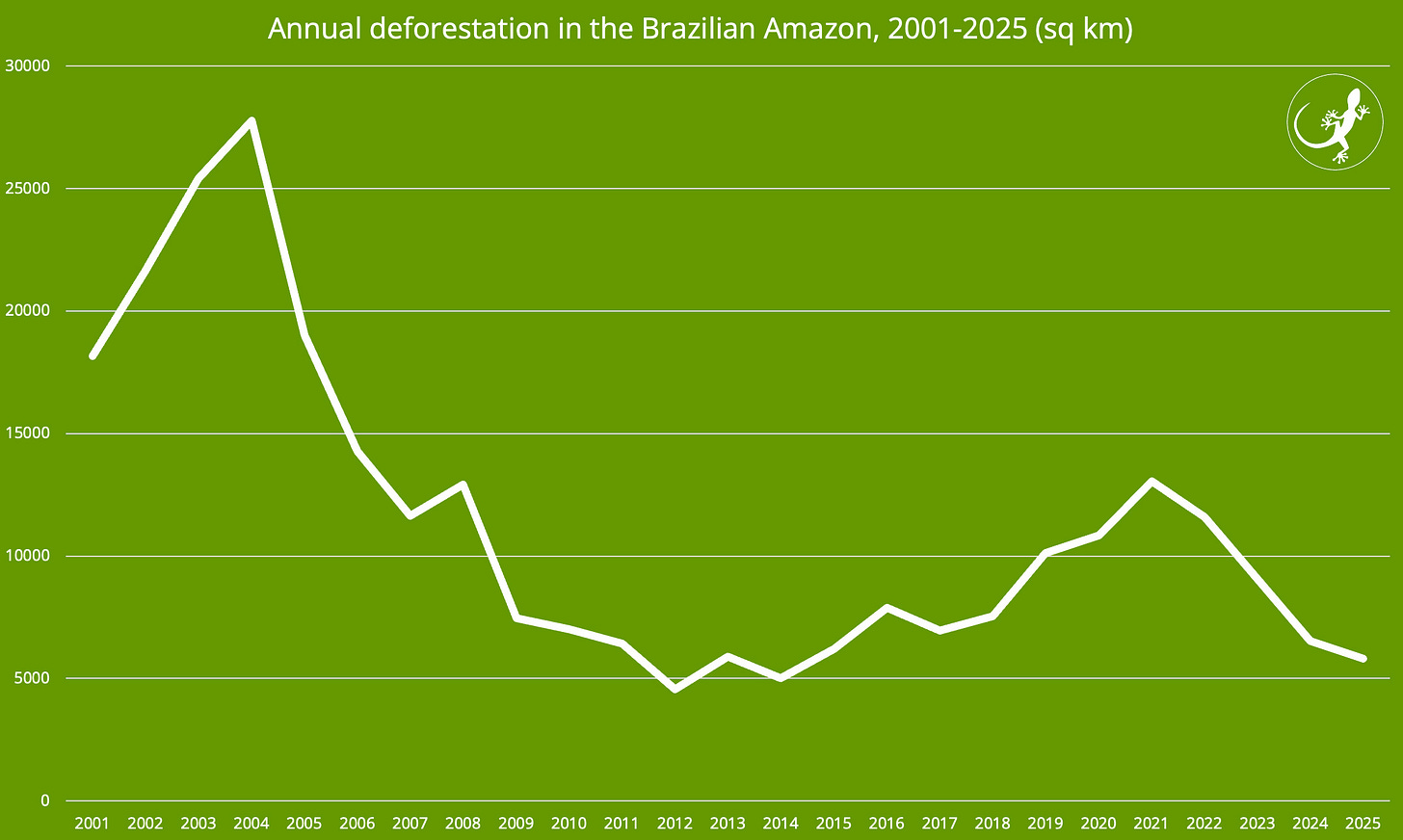

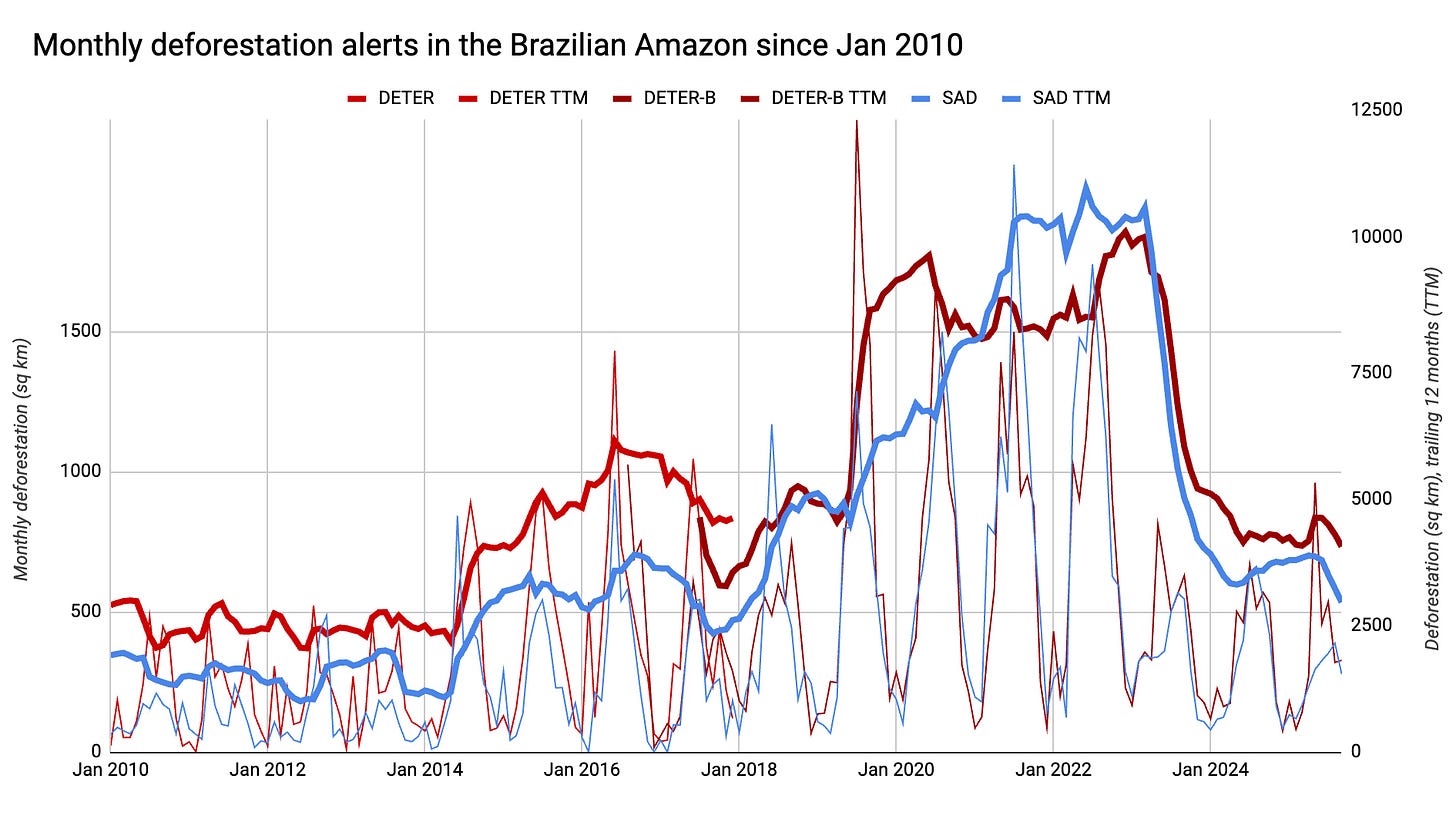

As the world’s attention turns toward COP30 in Belém next month, the story of Brazil’s Amazon is shifting—though not quite in a straightforward way. According to the government’s satellite-based monitoring system, INPE’s PRODES, deforestation in the region known as the “Legal Amazon” totaled 5,796 square kilometers for the 12 months ending July 31st, 2025. That’s 11% drop from 6,518 square kilometers in the same period a year earlier and the lowest annual tally since 2014. Meanwhile, the Brazilian NGO Imazon independently estimated a similar decline using its near-real-time detection system, SAD.

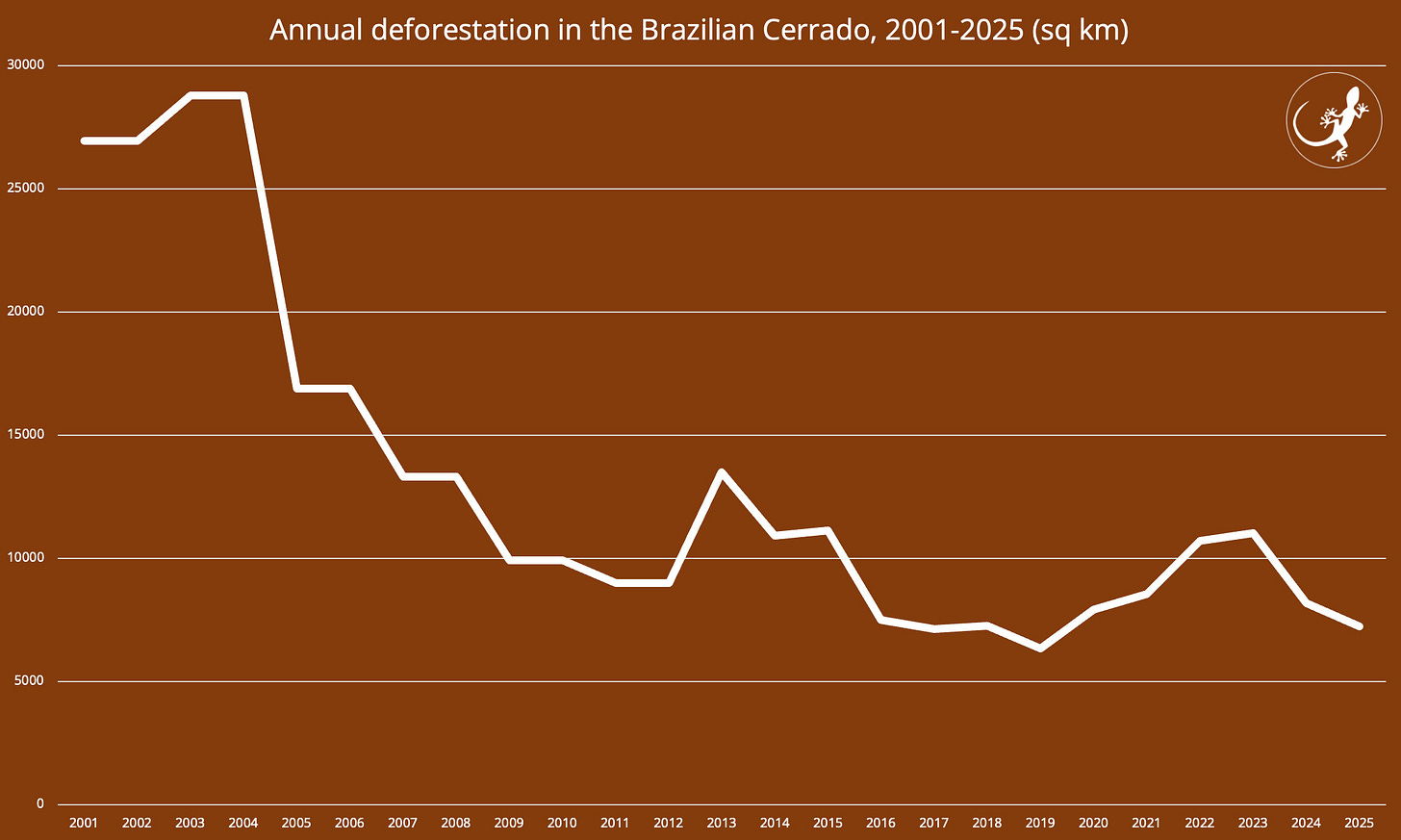

Deforestation also fell in Brazil’s Cerrado, a wooded savanna ecosystem that neighbors the Amazon rainforest. Clearing fell 11.5% to 7,235 square kilometers, a six-year low.

On its face, the data suggest progress. The steep fall under Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva—first during his initial presidency from 2003 to 2011, then again since January 2023—marks a clear reversal of his predecessor’s tenure, when deforestation soared as protections were rolled back and razing of forests were actively encouraged.

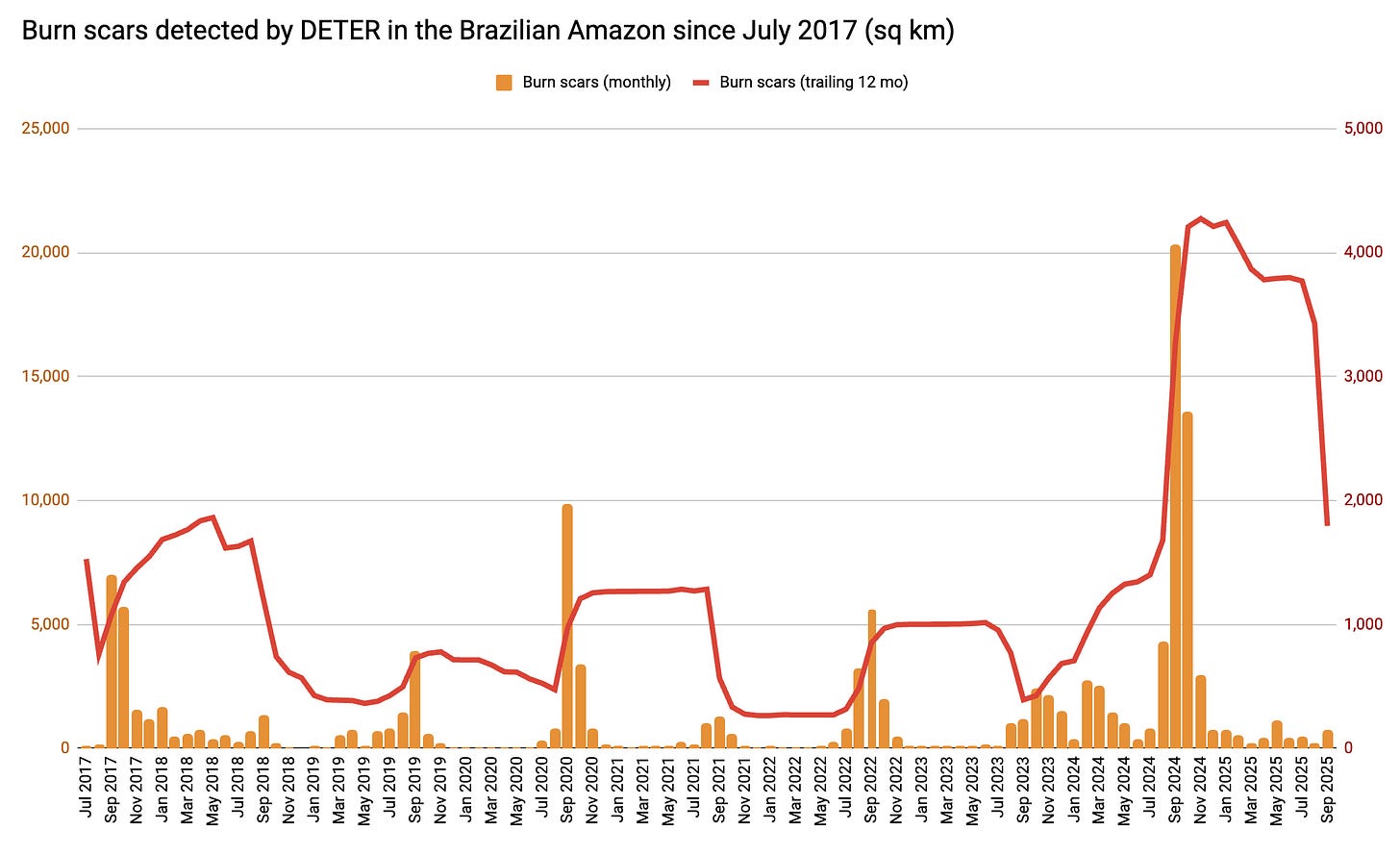

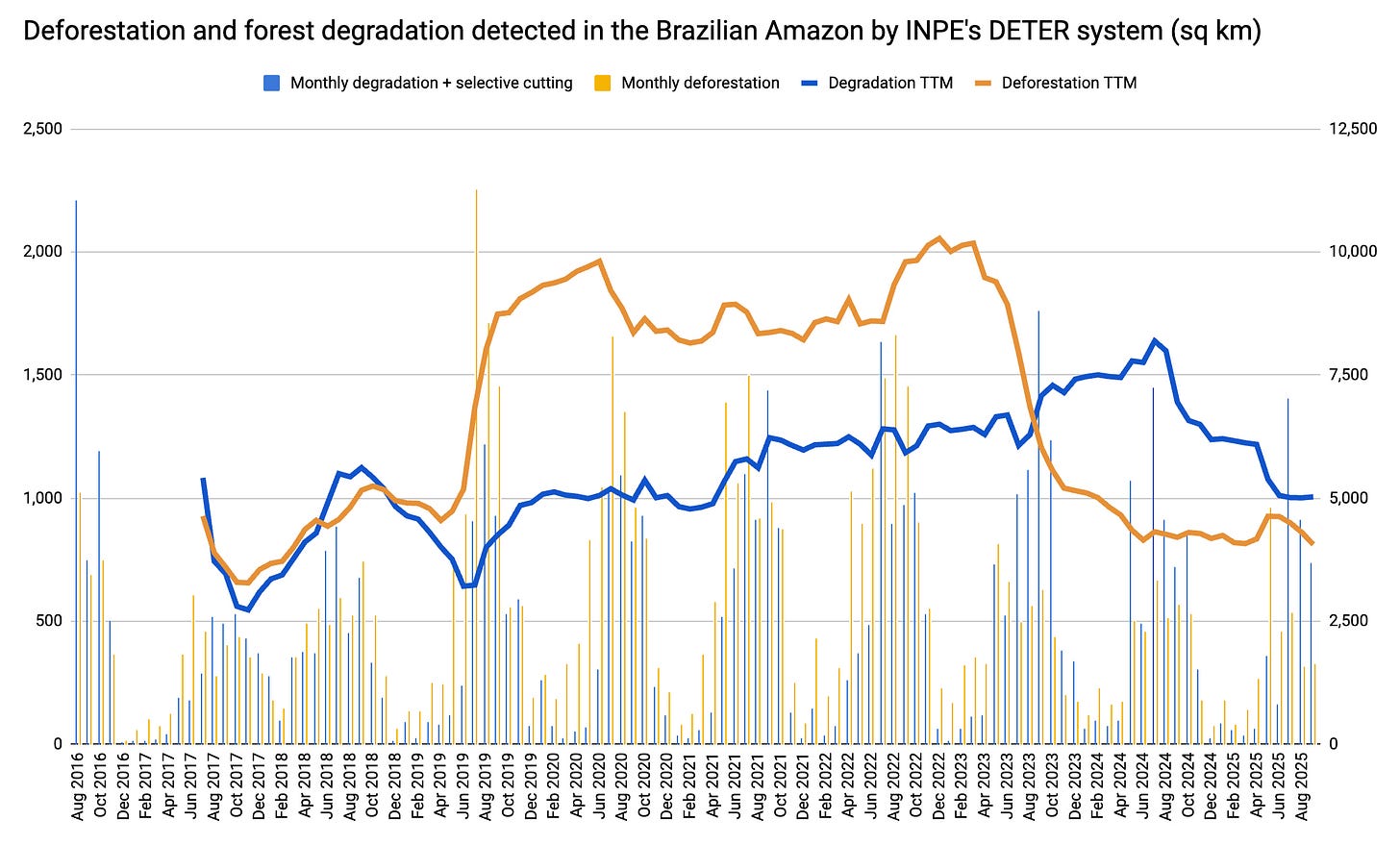

But while land clearing for farms has edged down, another threat looms. The nature of forest loss is changing, and fire now plays a far larger role. Forest degradation from selective logging, cumulative clearing, and the “fish-bone” sprawl of roads—combined with hotter, drier conditions—is turning wide stretches of the Amazon into tinder. Areas that once lay deep within the forest’s humid core are now drying out, leaving them vulnerable when agricultural burns escape control.

In 2024, Brazil was affected by an exceptional drought, which left rivers dry and temperatures set heat records. Brazil lost 2.78 million hectares of primary forest, the highest figure since 2019. Roughly 60% of that loss came from fire, which burned through six times more forest than the year before. Yet such losses are not counted in the official deforestation statistics, which—as in most countries—track clear-cutting rather than burning.

That distinction matters at the climate talks. This year, however, the burned areas detected by INPE’s DETER system are down 45%, from 39,310 square kilometers in the 12 months to September 2024 to 21,543 square kilometers in the same period ending September 2025. Forest degradation has also fallen sharply.

Still, the broader picture is complicated. Governance under Lula is having an effect: stronger oversight, renewed enforcement, stepped up funding, and clearer policy signals. Yet climate-driven forces and the legacy of past damage are pushing the Amazon toward a new regime of vulnerability. Loss from fire and degradation is becoming as consequential as direct deforestation.

As Brazil prepares to host COP30 in Belém in November, the Amazon’s fate sits high on the agenda. One major item will be the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF), a $125 billion fund first proposed by Brazil in 2023. If operational before 2030, it could generate around $4 billion annually for more than 70 tropical forest nations. COP30 may be its make-or-break moment.

Any optimism, though, will be tempered. New infrastructure projects, such as the controversial BR-319 highway through one of the Amazon’s most intact zones, remain under debate. Such developments can open access to settlers and speculators, accelerating forest loss. Gold prices are rising, governance in frontier regions is weak, and policy uncertainty lingers: Brazil suspended, reinstated, and re-suspended the soy moratorium, leaving its future unclear.

Why does this matter beyond the canopy? Because the Amazon is more than a forest. Its trees draw water from the soil, release it through transpiration, and create “flying rivers” that stabilize temperatures and carry rainfall across South America’s farmlands and cities. The forest cools local air and powers hydropower generation. Its decline erodes landscapes, livelihoods, and the planet’s climate balance.

So where do things stand now? Official data indicate that deforestation is slowing. Fire activity has dropped by nearly half. Yet the region remains in a fragile equilibrium, shaped by old wounds, new extremes, and shifting land-use pressures.

In other words, the Amazon is not out of the woods. At COP30 Brazil will present a forest story of progress—but also of peril. What matters now for the Amazon is whether the downward curve continues, and whether policy, finance, and on-the-ground governance can keep pace with a changing climate and evolving threats.

Other pieces:

A fisheries observer disappeared at sea. His family still waits for answers

He was sent to sea to watch others. To count the fish, record their fate, and make sure no one took more than they should. The job was meant to be routine: clipboard, samples, and a small bunk on a ship. Instead, it was perilous. Two years ago, somewhere off Ghana’s coast, the watcher disappeared. The watcher’s name was Samuel Abayateye, 38, a father of two. He was a fisheries observer, one of a small group of civilians assigned by Ghana’s Fisheries Commission to monitor industrial vessels at sea. They are meant to serve as the state’s eyes. The work is isolated and often tense. Observers live among the crews they are meant to report on, sometimes for weeks. The greater danger is not the sea itself, but what happens when an observer witnesses something he should not ignore.

Belize’s blue reputation vs. reef reality: Marine conservation wins, and what’s missing

Belize sells itself as a small-country answer to a big problem: how to keep the sea alive and the people who depend on it working. The pitch is strong. A debt-for-nature “blue bond” shaved public debt and created a 20-year conservation finance stream. Targets for 30% ocean protection by 2026 are now embedded in policy. The press has been kind. So have donors. Yet beneath the awards and ribbon cuttings sits a harder question: do the reefs and fish show it? And are day-to-day rules on the water keeping pace with the promises on paper?

he long-tailed macaque has lost a battle for its survival — but won one for scientific integrity, reports Mongabay’s Gerald Flynn. In early October, the IUCN, the global wildlife conservation authority, reaffirmed the species’ endangered status, rejecting an appeal by the U.S. National Association for Biomedical Research (NABR). The lobby group had argued that the listing impeded vaccine and drug development, since laboratories rely heavily on macaques for testing.