A slowdown, not salvation: what new extinction data reveal about the state of life on Earth

For decades, biologists have warned that humanity is precipitating a sixth mass extinction. By some estimates, species are vanishing at up to a thousand times the natural background rate. Yet a new study in Proceedings of the Royal Society B suggests the picture is more complicated. Extinctions, it finds, may have peaked a century ago—and declined since.

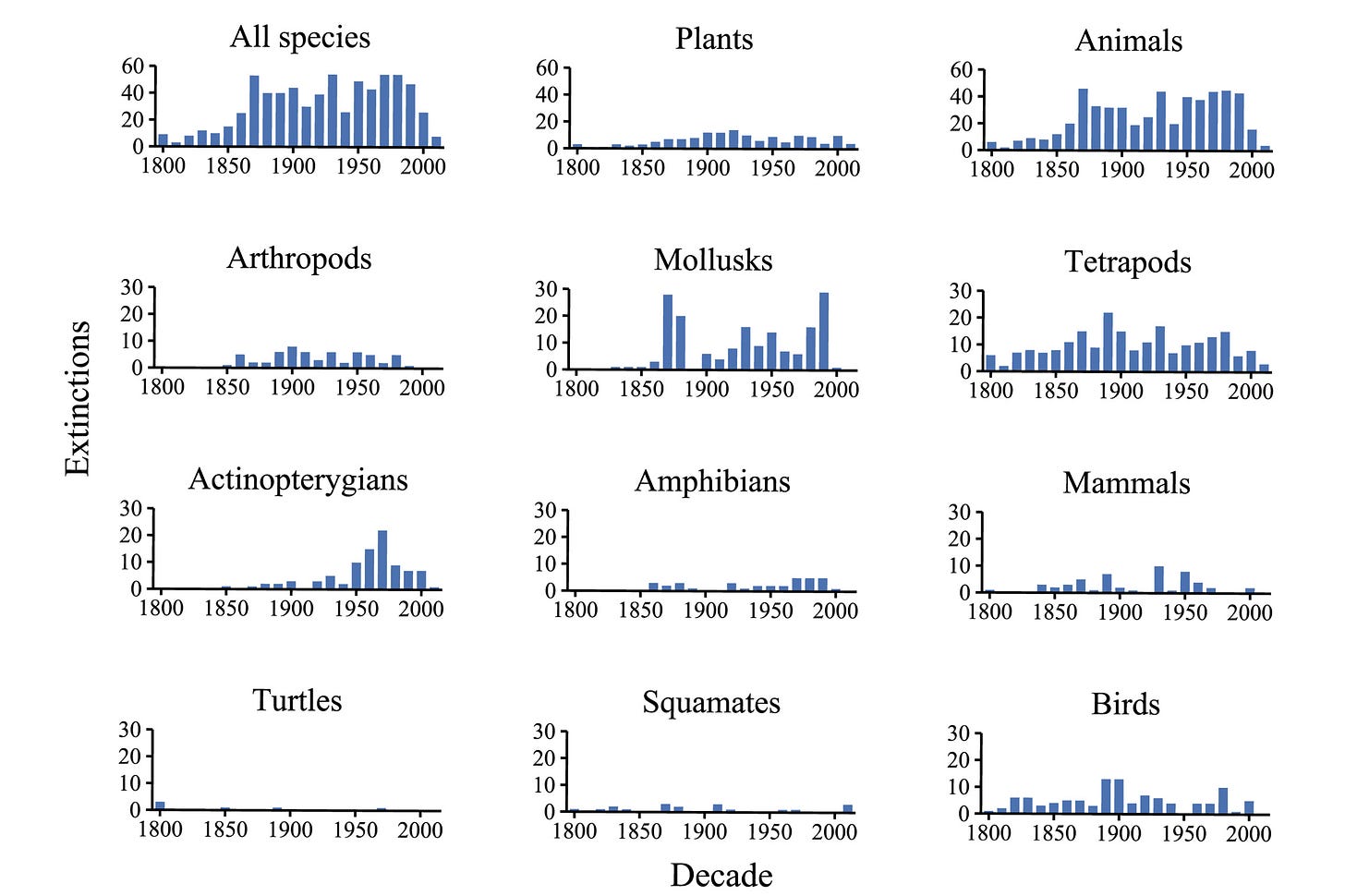

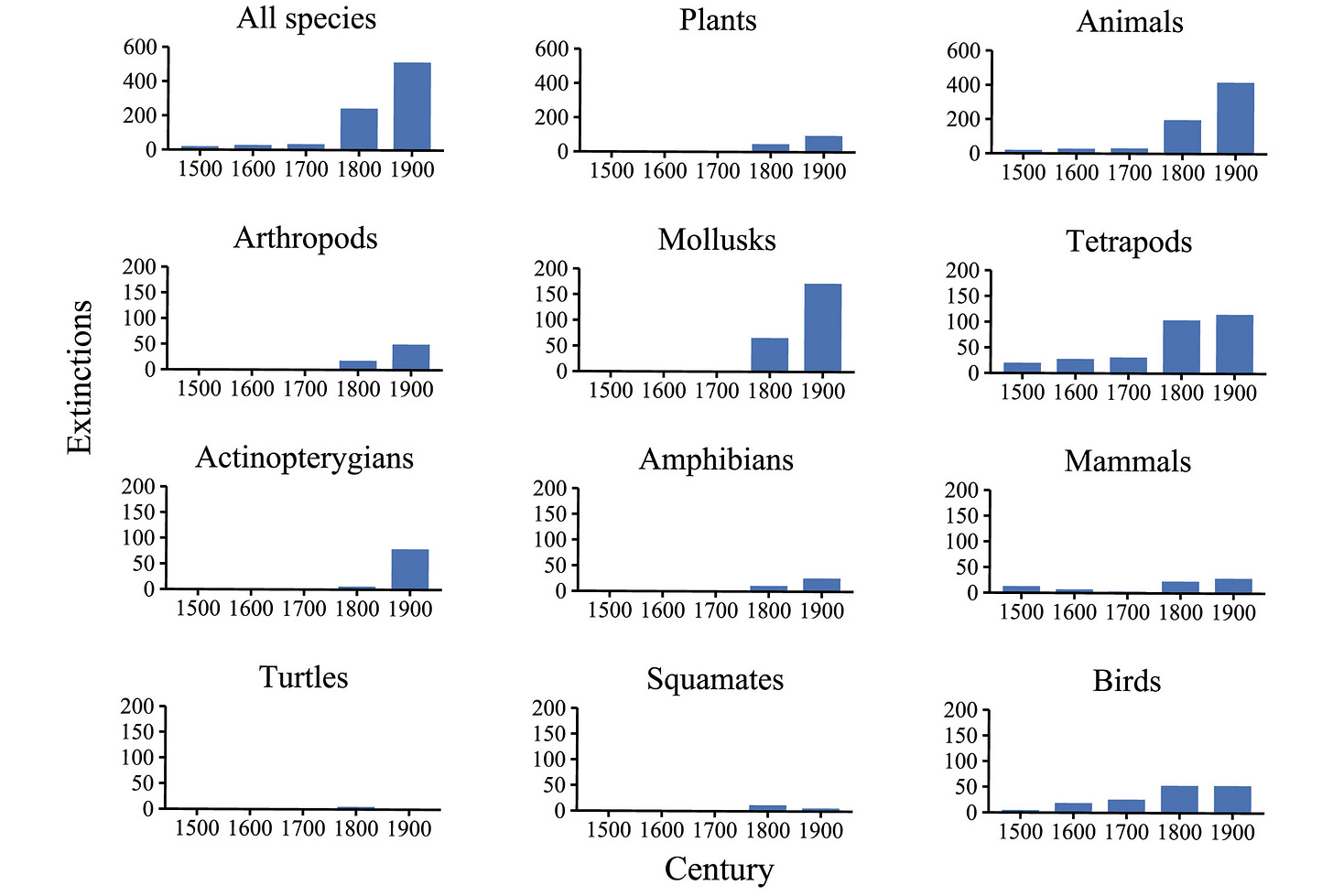

Kristen Saban and John Wiens of the University of Arizona examined 912 documented extinctions among plants and animals over the past 500 years. Their analysis, covering nearly two million assessed species, shows that losses rose steeply through the 1800s and early 1900s before slowing. Extinction rates for vertebrates, arthropods, and plants have generally decreased over the past century. The trend runs counter to the popular narrative of an accelerating biodiversity collapse.

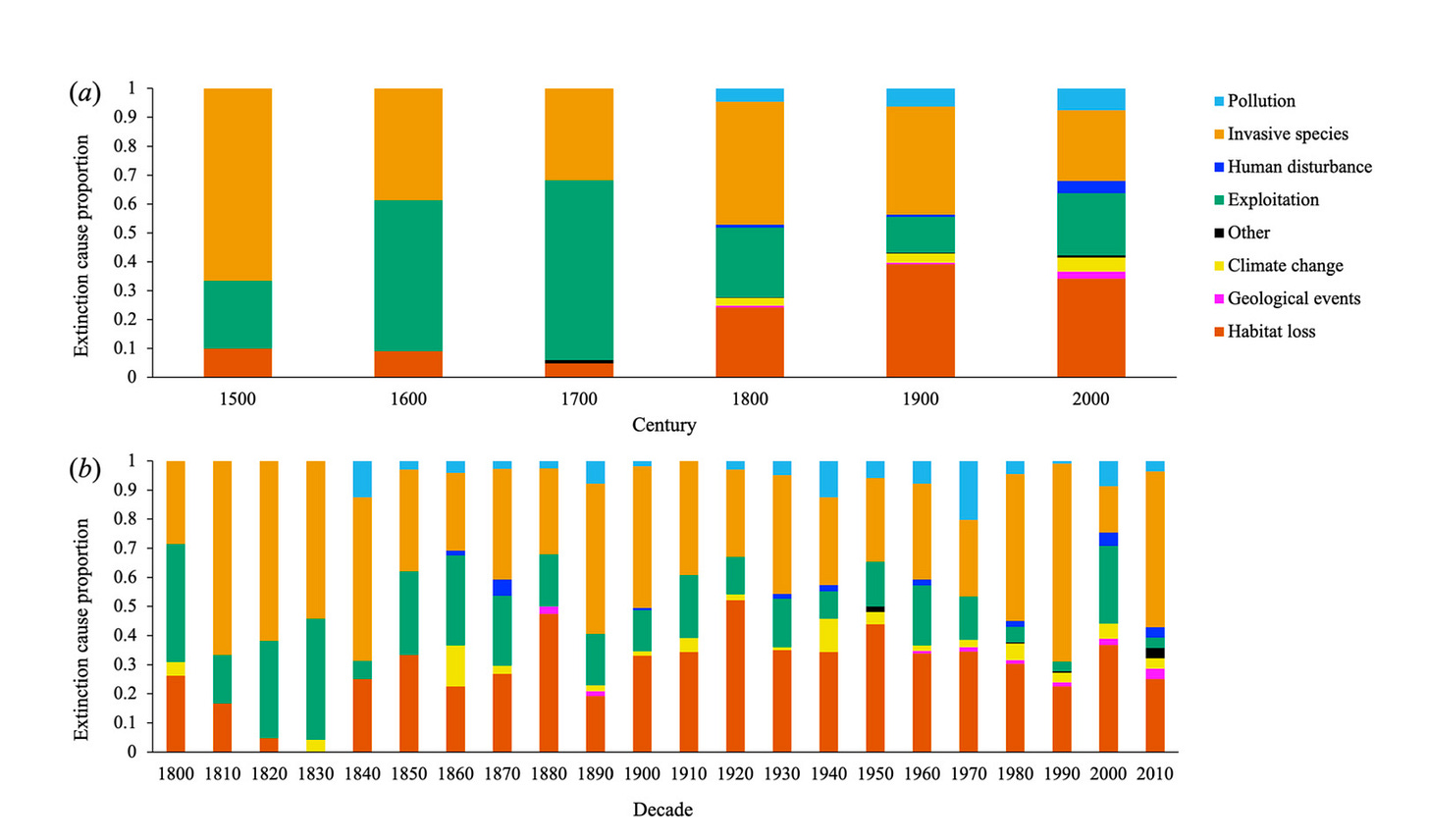

That finding, however, offers little comfort. The apparent lull in recorded extinctions may reflect where and how humans look, not a reprieve for nature. Most known extinctions occurred on islands, where invasive rats, pigs, and goats devastated native fauna and flora. Today’s drivers—deforestation, pollution, and climate change—are concentrated on continents, where declines in abundance and habitat fragmentation often precede total disappearance. As Wiens cautions, “past extinctions do not reflect current and future threats.”

The trouble with extrapolation

The study challenges a core assumption behind forecasts of mass extinction: that historical losses predict what comes next. When the authors compared past extinction rates to the proportion of species now listed as endangered by the IUCN, they found no strong relationship. Mollusks, for example, have suffered the heaviest recorded losses, whereas arthropods—77% of all animal species—remain poorly studied but largely uncounted. Only about 7.5% of known plant and animal species have been formally assessed.

Such gaps make projections hazardous. Most past extinctions were triggered by invasive species on islands; most present threats stem from habitat loss on continents. In the last 200 years, there has been no clear signal of extinctions linked to climate change—though that is widely expected to change as temperatures rise. The danger, Saban argues, lies not in overreacting but in misunderstanding. “It’s important that we talk about biodiversity loss with accuracy,” she said, “that our science is rigorous in how we’re able to detail these losses and prevent future ones.”

The geography of loss

Of the 912 species in the dataset, nearly two-thirds were confined to islands. The Hawaiian archipelago alone accounted for almost a quarter of all island extinctions. Freshwater species, too, were hit disproportionately hard: three-quarters of continental extinctions occurred in rivers and lakes. By contrast, marine losses were rare—at least so far.

Extinction causes varied with geography. On islands, invasive species were the leading culprits; on continents, habitat destruction dominated. Exploitation, pollution, and climate change played smaller but growing roles. The pattern mirrors a broader shift from localized ecological disruption to global environmental transformation. The authors found that extinctions from habitat loss and climate change have increased significantly over time, while those from overharvesting and invasive species have declined.

Conservation’s mixed record

The findings arrive about a year-and-a-half after an analysis published in Science by Penny Langhammer and colleagues, which offered a counterpoint to despair. Reviewing 665 conservation trials, they found that two-thirds of interventions either improved biodiversity or slowed its decline. Efforts such as invasive species eradication, habitat restoration, and protected-area management were especially effective. The largest measurable benefits came from programs on islands—where invasive control has rescued many species from the brink.

The meta-analysis underscored that conservation can work when done well. But success stories remain scattered, and the scale of response lags far behind the scale of loss. The authors noted that protected areas vary widely in effectiveness, with enforcement and funding often determining outcomes. “The takeaway,” they wrote, “is not that conservation has failed, but that it must be massively scaled up.”

From extinction to erosion

Even if outright extinctions have slowed, life’s fabric continues to fray. Many species persist only as ghosts of their former abundance. In long-lived animals, the disappearance of elders—those that remember migration routes, breeding sites, or drought refuges—hollows out the knowledge that sustains populations. Studies of elephants, corals, and fish show how the loss of the oldest individuals undermines resilience.

Likewise, research in Nature earlier this year found that human pressures—from land-use change to pollution—are not only reducing species numbers but transforming the composition of ecosystems. Communities are becoming unrecognizable, with generalists replacing specialists and local diversity falling by about 20% on average. The crisis, in other words, is not confined to extinction; it extends to the reshaping of life itself.

A cautious hope

Taken together, the new analyses suggest a more nuanced view. The worst predictions of runaway extinction may be premature, but complacency would be perilous. Species losses have slowed largely because humanity has already scoured the most vulnerable corners of the planet—and because conservation has, at times, worked. Yet the fundamental pressures—habitat destruction, climate instability, pollution—are intensifying across the continental heartlands that harbor most of Earth’s life.

The implication is not that the crisis has passed, but that its nature has changed. Extinction, once driven by rats on islands, is now driven by bulldozers and carbon in the atmosphere. The difference is scale—and reversibility. Targeted action can and does save species; protecting and restoring ecosystems may yet preserve the conditions for life to flourish.

As Saban put it, “If we’re saying that what is happening right now is like an asteroid hitting Earth, then the problem becomes insurmountable.” Her point is not to downplay the danger but to make it tractable. Catastrophe is not destiny; it is a choice. The task, as ever, is to keep life’s thread from breaking.

Citations:

Keck, F., Peller, T., Alther, R. et al. The global human impact on biodiversity. Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-08752-2

Kopf at al. Loss of Earth’s old, wise, and large animals. Science. 21 Nov 2024 DOI: 10.1126/science.ado2705

Langhammer, P. F., Bull, J. W., Bicknell, J. E., Oakley, J. L., Brown, M. H., Bruford, M. W., … & Brooks, T. M. (2024). The positive impact of conservation action. Science, 384(6694), 453-458. DOI: 10.1126/science.adj6598

Saban, Kristen E.; Wiens, John J (2025). Unpacking the extinction crisis: Rates, patterns, and causes of recent extinctions in plants and animals. Proceddings of the Royal Society B 292: 20251717. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2025.1717

Farewells to lost and almost lost species (From the archive

)

An obituary for the vaquita (2024)

This piece was supposed to publish on Thursday. Whoops!

Holy moly, this: "Catastrophe is not destiny; it is a choice. The task, as ever, is to keep life’s thread from breaking."